The American West is distinctive in many ways--from its expansive prairies and towering mountains, to its red-rock canyons and flat-topped buttes. Yet one factor above all else sets it apart from other geographic regions of the United States: its lack of precipitation. The West seemed so parched and desolate to 19th-century explorers that maps labeled it the Great American Desert. Today, we still know parts of it as Death Valley, a place so hot and dry that visitors are advised to drink at least one gallon of water a day to replace loss from perspiration.

Lack of rainfall always has been a defining problem in the American West. Long before Europeans arrived, predecessors to the Hohokam people migrated from central Mexico to southern Arizona, bringing domesticated crops and their knowledge of irrigation with them. The Hohokam created an extensive canal system and irrigated thousands of acres along the Salt River. Their descendants, Akimel and Tohono O’od, constructed networks of diversion dikes to capture runoff rainwater to cultivate their fields. When the Spanish arrived in the 17th and 18th centuries, mission priests enhanced Native American efforts by expanding and building new rock dams and small, earthen reservoirs.

In the 1840s, members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Mormons, migrated to the West and settled in small villages surrounded by intensively cultivated fields. The Mormons succeeded by working as a community and putting aside individual interests for the greater good of all. Their success in Utah demonstrated that American homesteaders could flourish in the desert. Despite differences in the social response to creating a vibrant farming economy, from the beginning, American settlers in the West recognized that successful farms usually depended on irrigation. As early as 1867, bills were introduced in Congress to encourage irrigation and reclamation of unproductive land and, in 1877, the Desert Land Act linked irrigation to grants of public land.

Congress also authorized studies of the West’s geology and water supply, which culminated in comprehensive reports. Most influential was John Wesley Powell’s 1878 Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States , in which he called for planned development of water and land resources in the West. Powell, famous for his explorations of the Colorado River, identified the 100th meridian, an imaginary longitudinal line running through the heart of the Dakotas and south through Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma, and then into Texas, as the point roughly dividing the moist East from the arid West. East of the line, annual precipitation exceeds 20 inches, making it possible to grow crops without irrigating. West of the line (with exceptions such as the Pacific Northwest), annual precipitation measures below 20 inches and can drop to under 5 inches in places such as Nevada’s Carson Desert. For Western settlement to succeed, Powell argued, the Federal Government must control the West’s rivers, irrigate its arid lands, and equitably distribute its water. In 1888, Congress appropriated $100,000 for Powell and his men at the decade-old U.S. Geological Survey to begin surveying places for possible irrigation works.

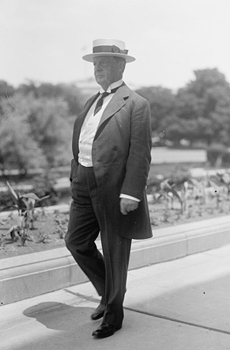

The movement calling for Federal involvement in reclamation found a strong advocate in Francis G. Newlands, who moved to Nevada in 1888 and soon launched the Truckee Irrigation Project, which he envisioned would create a “new” Nevada through irrigation. Like many other private projects, however, it fell flat, doomed by squabbling financiers and Nevada legislators. In 1893, when Newlands became Nevada’s representative in Congress, he still believed in his dream for Nevada, but now he was in a position to secure Federal help to make it come true.

It wasn’t, however, until the ascension to the presidency of the progressive Theodore Roosevelt (upon the assassination of William McKinley in September 1901) that Newlands and Federal reclamation received the boost they needed to overcome opposition. On June 17, 1902, the very day the bill landed on his desk, Roosevelt signed the Reclamation Act, also known as the Newlands Act after the congressman who had championed it. Advocates envisioned reclamation as a way to transform arid land into productive farms that would support families and bring economic stability to the West. That, in turn, would create new markets and extend prosperity to the nation. Many people, including Roosevelt, regarded the West’s rivers as an untapped resource that was literally running to waste. Why not harness this “wild” water to meet humanity’s needs?

The Reclamation Act of 1902 created the U.S. Reclamation Service (later changed to Bureau of Reclamation) and committed the Federal Government to construct and maintain “irrigation works for the storage, diversion and development of waters”--meaning dams, reservoirs, and canals--to irrigate arid and semiarid lands in 16 Western states and territories: Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. (Some of these states were still territories in 1902. Texas was added as a reclamation state in 1906.) The Reclamation Act established a special “reclamation fund,” intended to pay for the construction of the dams and canals needed to irrigate the West. Money in the fund would come, not from the U.S. Treasury, but from the sale of public lands. The Reclamation Act limited people on Reclamation projects to 160 acres, required residence on the property, and use of at least half of the land for agriculture. A key provision stipulated that those using the water had to repay the government’s construction costs within 10 years.

The Reclamation Act’s 160-acre provision, which followed a standard set by the 1862 Homestead Act, failed to recognize that some Western land was so inhospitable that it was more suited to grazing than farming and that 160 acres wasn’t enough for success in parts of the West. John Wesley Powell, in fact, recommended that up to 2,560 acres of public land be allowed to individual settlers, advice that was ignored. Such hard Western realities would present a learning curve for Reclamation during its early years.

The Federal Government had long subsidized internal public works, from building roads and harbors to pulling snags from rivers, but the Bureau of Reclamation was an unprecedented intervention in water matters. Many historians view it as the final piece of a government land policy rooted in Jeffersonian ideals of the yeoman farmer as the bedrock of democracy. The Reclamation Act of 1902, as had the Homestead Act of 1862, aimed to serve the nation’s social goal of settling families on the land. Beyond the 100th meridian, that goal depended on water, and a reliable flow of water, even for farmers who lived along a stream, was difficult to come by. Even if a farmer managed to plug a freshet and create a stock pond, he needed a canal to get the water to his fields. That required money and expertise beyond the reach of most individuals.

In the 1870s and 1880s , hundreds of private irrigation companies tried to reclaim the West’s arid lands, only to collapse from lack of know-how, profiteering, chaotic Western water laws, drought, harsh winters, or the devastating depression of the 1890s. Private efforts that did succeed proved it was possible to make the desert bloom, but large-scale projects presented great financial risk, making private capital hesitant to invest. In Wyoming, for example, even a man as famous and wealthy as William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody gave up on his dream of using Shoshone River water to irrigate 60,000 acres around his newly founded town of Cody. When he and his business partner investigated the feasibility of the project, they decided it was cost prohibitive. The Wyoming State Board of Land Commissioners then turned to the U.S. Congress for help, and Buffalo Bill, in 1904, transferred his water rights to the Federal Government, which took over the project.

Also instructive is the story of Sheriff Pat Garrett, well-known killer of Billy of Kid. After settling down, Garrett envisioned transforming the Pecos River Valley in the southern New Mexican desert into small, prosperous farms. He enlisted financial help from well-heeled businessmen and, by 1890, the Pecos Irrigation and Investment Company dammed the Pecos River and constructed the core of a complex irrigation system. Investors soon discovered, however, that the irrigation system was costing them more than they had expected and, in 1905, they sold the entire network to the new U.S. Reclamation Service. Countless other private attempts, as well as a few state efforts, to irrigate slices of the West also collapsed. As much as the West prided itself on its stubborn individualism, making the desert bloom seemed a task too big for even a hardy Westerner. Slowly, it became apparent that the Federal Government, with its capital, engineering skills, and organizational structure, was the one entity that seemed able to take on the gargantuan task of transforming the desert and succeeding.

With formation of the U.S. Reclamation Service in 1902, the work went forward with astonishing speed. The very next year, five projects were authorized: the Salt River Project in Arizona Territory; Milk River Project in Montana; Truckee-Carson (Newlands) Project in Nevada; Sweetwater (North Platte) Project in Nebraska; and the Gunnison (Uncompahgre) Project in Colorado. Six more were approved in 1904 and nine more in 1905. By the end of 1907 there were 24 authorized Reclamation projects, at least one in each of the original 16 Reclamation states, with the exception of Oklahoma. The Reclamation Service excelled in dam building, constructing some of the most impressive water diversion structures and the largest and highest dams in the Western Hemisphere, like Theodore Roosevelt in Arizona, Arrowrock in Idaho, Elephant Butte in New Mexico, Pathfinder in Wyoming, and Belle Fourche in South Dakota. In Nevada, construction of Derby and Lahontan dams spurred the growth of desert towns such as Fallon, which prided itself on the juicy cantaloupes grown on irrigated lands. In Colorado, the Gunnison Tunnel holed right through the steep walls of the Black Canyon, and Wyoming’s Shoshone Dam, completed in 1910, fulfilled Buffalo Bill’s dream. (In 1946, Shoshone Dam was renamed Buffalo Bill Dam in honor of Cody.)

During its first quarter century, the Bureau of Reclamation became the foremost builder of water storage, diversion and transmission projects in the world. While these early projects did succeed in irrigating arid lands and spurring development, the number of acres reclaimed never met projections, and problems with everything from water-logged lands to high construction costs and disgruntled farmers who couldn’t make their payments led in 1923 to a Fact Finder’s Commission, directed to analyze the Reclamation program, including cost overruns. While the Bureau had spent $135 million on its projects, repayments totaled less than $10 million. Reorganization followed and, with it, a new name: the Bureau of Reclamation. Ended was the strict repayment structure for farmers, who now were offered loans to provide the time and aid necessary to make their farms productive. In the future, the sale of electricity would cover a large portion of costs.

A signal of things to come was creation of the Colorado River Compact, which involved management of the entire Colorado River Basin. The compact provided a formula for settling disputes over water rights among the seven states in the Colorado River’s drainage area (Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming). With the compact and approval in 1928 of the Boulder Canyon Project, centered on Hoover Dam , the Bureau of Reclamation enlarged its mission and embarked on huge, multi-purpose projects that aimed to do more than irrigate arid farmland. Its new projects focused on hydroelectric power as a principal benefit. This came about after an intense public debate on whether the Federal Government should become involved in public power production or whether that should be left to private enterprise. In 1939, Congress legitimized this new multi-purpose direction for the Bureau of Reclamation, whose future projects would address not only irrigation, but hydroelectric power, navigation, flood control, and municipal and industrial water supplies. Importantly, the sale of electricity provided revenue to pay for ever-larger Reclamation projects.

Even as President Herbert Hoover signed the first appropriation bill for Hoover Dam in the summer of 1930, the nation was falling into deep economic trouble. As it turned out, the Great Depression paved the way for some of Reclamation’s greatest achievements as the new administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt launched program after program in an attempt to spur the economy by “priming the pump” and providing jobs for out-of-work Americans. Unprecedented funds flowed to the Bureau of Reclamation as it became a key player in the New Deal’s Public Works Administration (PWA), which spent “big bucks on big projects,” such as building the Lincoln Tunnel, the causeway linking the Florida Keys to the mainland, and big dams, which stood out as monuments to a prosperous future. By the outbreak of World War II, the PWA had authorized 37 Reclamation projects, 13 of which were major storage dams, including Grand Coulee on the Columbia and Shasta in California’s Central Valley.

The Bureau of Reclamation also became involved in government programs to resettle struggling farmers on irrigated lands and found work for unemployed young men with the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), who lived at 34 camps set up on Reclamation sites. They lined canals with riprap to prevent erosion, cleaned drainage ditches, built roads, constructed recreation amenities, and cleared reservoir sites of brush and trees. In 1938 alone, they contributed almost a million man days to Reclamation projects. Unlike the CCC and Works Progress Administration, which provided jobs for millions of the unemployed, the PWA was not a work-relief program, although its projects, which were put out for bid to private companies, helped keep people off relief.

A Reclamation project funded by the PWA could involve more than a big dam. In January 1935, for instance, the PWA allotted funds for a study that led to the ambitious Colorado-Big Thompson Project, launched in 1937 and involving the construction of dams, dikes, reservoirs, powerplants, pumping plants, pipelines, tunnels, transmission lines, substations, and other structures that spread over 250 miles. A key feature was the 13-mile-long Alva B. Adams Tunnel. Constructed beneath Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado, it not only transferred water from one watershed to another, but cut right through the Continental Divide, taking water from the Western Slope of the Rocky Mountains to the more urban Front Range on the Eastern Slope. Today, 11 cities depend on the project for municipal and industrial water, as well as hydroelectric power. The project offers recreation at its reservoirs and also provides supplemental water to irrigate as much as 720,000 acres.

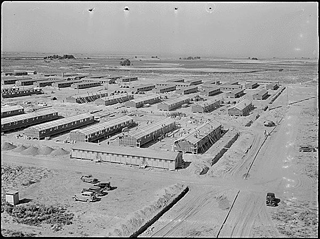

The coming of World War II placed the Bureau of Reclamation in still more new roles. In the frenzy following the December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor, the Federal Government relocated 120,000 persons of Japanese and Japanese American ancestry from the West Coast to 10 inland internment centers, three of which were established at former CCC camps on Reclamation land: at Tule Lake in northern California, Minidoka in Idaho, and Heart Mountain in northwestern Wyoming. While there, internees worked on Reclamation projects, building canals and ditches to irrigate their own fields and to help the war effort. Also assigned to camps, under the government’s Civilian Public Service program, were conscientious objectors who labored on Reclamation projects in Oregon, Colorado, and South Dakota. German and Italian prisoners of war also were detained on Reclamation project sites, including Minidoka in Idaho and Belle Fourche in South Dakota.

Reclamation projects played a huge role as the American defense industry revved up for the war effort. Grand Coulee Dam, completed in 1941 on the Columbia River in Washington, provided the enormous electrical power needed to produce aluminum, used in the building of warplanes and ships. In fact, one-half of the military planes produced in the United States during World War II depended on power from Grand Coulee Dam. It was power from Grand Coulee, as well, that charged the production of plutonium at the nearby Hanford Site, which figured prominently in the making of the atomic bomb.

As hundreds of thousands of people moved West to work in the war industries, cities grew, especially in the three Pacific Coast states, where population mushroomed by a third between 1940 and 1945. In northeastern Washington, for instance, the Spokane Army Air Depot (today’s Fairchild Air Force Base) employed 10,550 civilians and 7,000 military personnel in repairing damaged aircraft. Meanwhile, the government built two nearby aluminum plants that were purchased after the war by the industrialist Henry J. Kaiser. Today, Kaiser Aluminum’s Trentwood plant continues to employ people in the Spokane Valley. In Seattle, Boeing’s Plant 2 employed thousands of workers to build the heavy, B-17 Flying Fortress and B-29 Superfortress bombers. Of the nearly 13,000 B-17s produced during the war, about half rolled out of the Seattle plant. In Southern California, San Diego, long a “Navy town,” seemed to mature overnight as it became the new headquarters of the nation’s Pacific Fleet and a training center not only for sailors, but for soldiers and Marines. Defense contractors went into high gear, including the Consolidated-Vultee Corp., which churned out B-24 Liberators. The city’s booming population so added to its water needs that San Diego, averaging only 9.9 inches of rainfall a year, feared a water shortage and began efforts to tap into Colorado River water by promoting the San Diego Project, with the first of two major aqueducts completed in 1947.

Reclamation’s early mission was rural--helping small farmers settle the land. But in the years before and after World War II, its job looked more and more urban, as did the West. By the year 2000, some 86 percent of Westerners lived in or near cities. Consider Las Vegas, a town of only 5,165 people when plans were being laid for Hoover Dam in 1930, a year when the population of the entire West was only 11 million people. After World War II, tourism took over as Las Vegas’ largest employer and, beginning in the 1980s, unprecedented growth began. The 2010 census recorded just shy of 2 million residents in Clark County, all but 3 percent of whom live in the Las Vegas area, a city that depends on Hoover Dam’s Lake Mead for 90 percent of its water supply. In recent years, facing a prolonged drought, Las Vegas and other cities in the Southwest have undertaken extensive conservation programs, but many question the sustainability of such large-scale growth.

Environmental concerns surrounding Bureau of Reclamation projects are not new (public outcry about conservation of Lake Tahoe dates to 1908), but concerns accelerated after World War II as the nation prospered. National parks became more of a travel destination, and Americans became more educated about man’s relationship to the environment. A sign of changing attitudes surfaced in the early 1950s when conservation groups tried to stop the slated construction of Echo Park Dam, which would have flooded miles of the Green and Yampa rivers in Dinosaur National Monument on the Colorado-Utah border. A compromise was struck, Echo Park spared, and Glen Canyon Dam, on the Colorado River in Arizona, constructed instead. As public consciousness and political support for environmental protection grew in the 1960s, Federal legislation resulted: the Wilderness Act of 1964, the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act in 1965, the National Historic Preservation Act in 1966, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968, the Endangered Species Act of 1973, and others.

Today, as it was in 1902, water remains indispensable to life in the American West. But populating the West, which grew by 32 percent in the last quarter of the 20th century, no longer is Reclamation’s goal. The question, as Lawrence J. MacDonnell writes in From Reclamation to Sustainability , is “not how to attract people to the West but how to maintain the quality of life that is attracting them.”

With the West’s rivers and streams extensively developed, the era of large dam construction is over. The last of Reclamation’s major authorizations, the Animas-La Plata Project in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, has been constructed. But that doesn’t mean Reclamation’s work is done. Projects involving dam maintenance and safety, as well as rural water projects remain. In 1999, for instance, the spillway at Tieton Dam , west of Yakima, Washington, was repaired and, in 2008, the spillway tunnel at Yellowtail Dam in Montana. In an age when a variety of interests compete for the limited water resources of the West, Reclamation aims to balance those needs and emphasize conservation, water recycling, and reuse. In the summer of 2010, through its WaterSMART program, for example, grants were issued to water districts, municipalities, and Indian tribes across the West who were seeking to achieve a sustainable water strategy. Projects ranged from a study to identify the potential impact of climate change on fish and wildlife habitats in Nevada’s Truckee River Basin, to efforts by a Port Isabel, Texas, water district to save electricity by making improvements to its non-potable water system.

Visit the National Park Service Travel Bureau of Reclamation's Historic Water Projects to learn more about dams and powerplants.